The 1932 Ford Hunger March massacre:The unemployed get bullets, not bread

Mattie Woodson tore off a piece of her dress and leaned down to wipe blood off the neck of Joe DeBlasio, desperately trying to save the life of the young demonstrator. It was too late. DeBlasio was dying. He lay in Miller Road in Dearborn, Michigan, just a few yards in front of the gigantic River Rouge complex of the Ford Motor Company. He had been shot when Dearborn police officers and thugs from Ford’s brutal “Service Department” opened fire on unarmed demonstrators. It was March 7, 1932. The protest which had originally been called “the Ford Hunger March” had just become a massacre.

DeBlasio was one of five people who died after being shot that day. Dozens of others were wounded. The Ford Hunger March took place in the midst of the Great Depression, just 28 months after the stock market crash of October 1929. The month of March 2012 marks 80 years since that massacre, but its effects can still be felt.

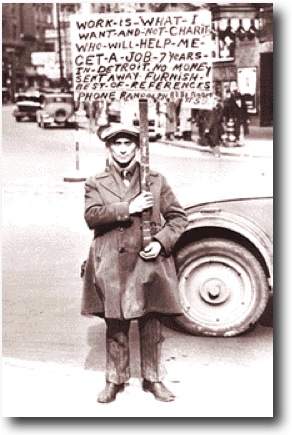

The Ford Hunger March was a response to economic devastation. No city in the United States was hit harder by the Great Depression than Detroit. By 1932, some 10,000 children huddled every day in Detroit’s bread lines. Eighty percent of the auto-building capacity lay idle. Wages had dropped 37 percent for those lucky enough to have a job. The average monthly caseload of the city’s welfare department had increased almost 10 times – from 5,000 cases in 1929 to nearly 50,000 in 1932. The Ford Hunger March was a response to economic devastation. No city in the United States was hit harder by the Great Depression than Detroit. By 1932, some 10,000 children huddled every day in Detroit’s bread lines. Eighty percent of the auto-building capacity lay idle. Wages had dropped 37 percent for those lucky enough to have a job. The average monthly caseload of the city’s welfare department had increased almost 10 times – from 5,000 cases in 1929 to nearly 50,000 in 1932.

The workers of the Detroit area responded by organizing Unemployed Councils. (There were about a dozen in and around Detroit.) During the brutal winter of 1931-32, representatives of these councils decided to organize a march in early spring to focus attention on Henry Ford and his huge River Rouge complex.

At the time, Henry Ford was the richest man in the world. He was also a vicious anti-Semite, an admirer of Hitler, and an ardent foe of unions. Built in the 1920s, the River Rouge site was the largest industrial complex in the world. It was located in Dearborn, a town whose mayor, police officers, and fire fighters answered directly to Ford.

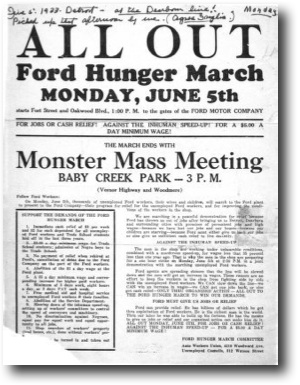

The Ford Hunger March was organized to press 11 demands, including jobs for the jobless; the seven-hour day; the end of speed-up; no racial discrimination; abolition of the Ford Service Department; and winter relief.

On March 7, 1932, the Unemployed Councils from inside Detroit led off the march from their assembly point on the city’s East Side. As their contingent marched west to Woodward Avenue and then south on Woodward, many people who had been standing on the sidewalks began to join in.

The marchers made their way to the old Detroit City Hall. There, Mayor Frank Murphy came out, waved, and declared, “I’m with you all the way.” Murphy assigned two motorcycle cops to escort the marchers to the city limit.

When the march got to the border with the city of Dearborn, about 30 Dearborn police officers on motorcycles and horses and in cars blocked their path. The Dearborn police ordered the marchers to turn back. They refused, and moved forward.

The police fired tear gas. Some marchers – desperate and angry – responded by throwing rocks and frozen mud. Near Gate No. 3 of the River Rouge complex, the demonstrators were bombarded by water from fire hoses and a barrage of bullets from Dearborn cops and Ford “security” thugs. When the shooting stopped, four demonstrators were dead. In addition to Joe DeBlasio, the slain included Joe York, Coleman Leny, and Joe Bussell. (Curtis Williams would die later.) Dozens of marchers were wounded.

On March 12, 1932, thousands of people marched solemnly down Woodward Avenue from the Institute of Arts to Grand Circus Park, where tens of thousands of people had  gathered. A funeral procession of 70,000 people then marched five miles to the Woodmere Cemetery, where DeBlasio, York, Leny, and Bussell were laid in a common grave – within sight of the smokestacks of the River Rouge complex. The cemetery would not allow Curtis Williams, an African-American, to be buried with his comrades. Williams’ ashes were scattered over the River Rouge plant from an airplane. gathered. A funeral procession of 70,000 people then marched five miles to the Woodmere Cemetery, where DeBlasio, York, Leny, and Bussell were laid in a common grave – within sight of the smokestacks of the River Rouge complex. The cemetery would not allow Curtis Williams, an African-American, to be buried with his comrades. Williams’ ashes were scattered over the River Rouge plant from an airplane.

Detroit’s workers turned their outrage into energy and that energy launched the organizing drives at the Big Three automakers. In 1937, following the sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan, the United Auto Workers successfully unionized General Motors and Chrysler. It wasn’t until 1941 – after a bitter battle -- that the Ford Motor Company finally sat down at the bargaining table with representatives of its workers.

Ford workers got their first union contract in the summer of 1941, just months before the United States entered World War II. The rulers of this country desperately needed “labor peace” during World War II and they achieved it. That peace continued for many years. For decades following World War II, most unionized workers could expect a wage increase with every new contract, and a steadily rising standard of living. Ford workers got their first union contract in the summer of 1941, just months before the United States entered World War II. The rulers of this country desperately needed “labor peace” during World War II and they achieved it. That peace continued for many years. For decades following World War II, most unionized workers could expect a wage increase with every new contract, and a steadily rising standard of living.

Some workers forgot the lessons of the massacre of March 7, 1932 during the good times after World War II. We need to remind ourselves of those lessons, because this year finds workers out in the cold again. The 76th anniversary of the Ford Hunger March finds workers shivering on the picket lines at American Axle Manufacturing. That company’s 3600 workers are fighting to stop their employer from slashing their wages in half. (And that proposal comes from a company that made $37 million in profit in 2007!)

Especially now – at a time of concession contracts, plant shut-downs, growing poverty, and turmoil in the stock market -- we would do well to remember both the defiance displayed by the members of the Unemployed Councils during the 1930s and their imaginative tactics. Labor needs to bring both qualities back again.

The articles on this page are written by Chris Mahin for the Education and Mobilization Department of the Chicago & Midwest Regional Joint Board of UNITE HERE and originally appeared on the Joint Board’s website.

Special thanks to Brother Mahin for allowing the Pennsylvania Federation access to his writings.

|