Texas pecan shellers strike for dignity in the midst of the Great Depression

They were some of the lowest-paid workers in the entire United States, but management claimed that they didn’t deserve more money. (Their employers said that the workers would just spend any raise on tequila and trinkets from the local dime stores.) No wonder the workers went on strike!

February 2008 marks exactly 70 years since the official beginning of the pecan shellers’ strike in San Antonio, Texas in 1938. That confrontation changed the face of organized labor in the Southwest.

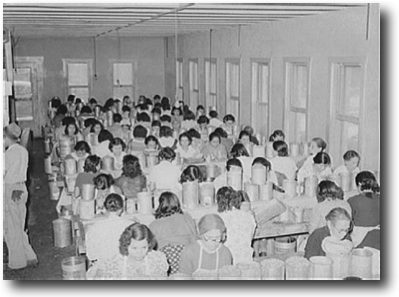

Pecan shelling was the largest industry in San Antonio during the Great Depression, employing 12,000 people. Ninety percent of the workers were women, most of them Mexican.

The shelling was carried out in 400 sheds scattered throughout the working-class neighborhoods of the West Side. It was common to find 100 shellers sitting around a long table working under poor illumination. There were no indoor toilets or washbowls. Ventilation was inadequate. A fine brown dust from the pecans permeated the air. This dust contributed to the very high death rate from tuberculosis in San Antonio, almost three times the national average.

Machines had been invented to crack and grade pecan nuts by the 1920s. However, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the shelling companies found it more profitable to hire people who desperately needed jobs, pay them low wages, and have them do all the work by hand. The shellers of San Antonio worked 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Often the individual worker made as little as $2.73 a week. When the owners announced a pay cut on January 31, 1938, these workers spontaneously walked out of the shelling sheds. The next day, the Texas Pecan Shelling Workers Union officially called a strike. The battle was on.

Conservative elements within San Antonio’s city government, police department, civic establishment, religious community, mass media, and trade union movement all combined in a nasty, underhanded, concerted effort to break the strike and isolate its leaders. No blow was too low.

The police made more than 1,000 arrests during the strike. The striking workers were attacked with tear gas, clubs, and baseball bats, and were subjected to arrests on ludicrous charges (such as obstructing the sidewalk where there was no sidewalk.) The strikers were confined in overcrowded jails where they were treated worse than hardened criminals.

Police Chief Owen Kilday claimed that only a few pecan shellers were participating in the strike. He asserted that what was really going on was an attempt to foment revolution, declaring “It is my duty to interfere with revolution.”

The pecan shellers were denounced by San Antonio’s two major newspapers – the Express and the Light. The American Chamber of Commerce, the Mexican Chamber of Commerce, the League of United Latin American Citizens, and Archbishop Arthur Jerome Drossaerts of the Roman Catholic Church all condemned the strike. The shelling was carried out in 400 sheds scattered throughout the working-class neighborhoods of the West Side. It was common to find 100 shellers sitting around a long table working under poor illumination. There were no indoor toilets or washbowls. Ventilation was inadequate. A fine brown dust from the pecans permeated the air. This dust contributed to the very high death rate from tuberculosis in San Antonio, almost three times the national average.

Machines had been invented to crack and grade pecan nuts by the 1920s. However, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the shelling companies found it more profitable to hire people who desperately needed jobs, pay them low wages, and have them do all the work by hand. The shellers of San Antonio worked 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Often the individual worker made as little as $2.73 a week. When the owners announced a pay cut on January 31, 1938, these workers spontaneously walked out of the shelling sheds. The next day, the Texas Pecan Shelling Workers Union officially called a strike. The battle was on.

Conservative elements within San Antonio’s city government, police department, civic establishment, religious community, mass media, and trade union movement all combined in a nasty, underhanded, concerted effort to break the strike and isolate its leaders. No blow was too low.

The police made more than 1,000 arrests during the strike. The striking workers were attacked with tear gas, clubs, and baseball bats, and were subjected to arrests on ludicrous charges (such as obstructing the sidewalk where there was no sidewalk.) The strikers were confined in overcrowded jails where they were treated worse than hardened criminals.

Police Chief Owen Kilday claimed that only a few pecan shellers were participating in the strike. He asserted that what was really going on was an attempt to foment revolution, declaring “It is my duty to interfere with revolution.”

The pecan shellers were denounced by San Antonio’s two major newspapers – the Express and the Light. The American Chamber of Commerce, the Mexican Chamber of Commerce, the League of United Latin American Citizens, and Archbishop Arthur Jerome Drossaerts of the Roman Catholic Church all condemned the strike.

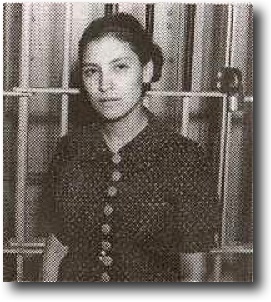

One of the weapons used against the strike was the tactic of Red-baiting. At the beginning of the strike, the strikers had unanimously elected as their spokesperson a young woman named Emma Tenayuca. A dynamic speaker with a magnetic personality, Tenayuca was a member of the small Communist Party chapter in Texas. The workers’ enemies attacked all the strikers because of Tenayuca’s political associations. In order to deprive the strike’s enemies of a pretext with which to attack the workers, Emma Tenayuca eventually decided to step aside from role as chief spokesperson for the strikers. (She continued as one of the strike’s most stalwart leaders on the ground.)

On March 8, 1938, the pecan shellers returned to work for the wages that originally sparked the strike – pending the decision of a three-person arbitration board. On April 13, 1938, the board rendered a decision giving the workers a slight wage increase and extending recognition to Local 172 as the workers’ legal bargaining agent.

On October 24, 1938, a new federal law went into effect raising the minimum wage. The Southern Pecan Shelling Company and the local union petitioned for an exemption to this minimum wage. When their requests were denied, the pecan shelling companies quickly began to mechanize.

By 1941, about 10,000 of the 12,000 unskilled workers who had made up San Antonio’s pecan shelling industry at the time of the strike had lost their jobs permanently. By 1948, Pecan Shelling Workers Union Local 172 had disappeared.

The massive job loss which followed the strike does not diminish the significance of the strike itself. The courageous fight of the pecan shellers of San Antonio paved the way for the battles waged by other agricultural and food workers in the Southwest. Their victories would never have been achieved without the valiant example set by the pecan shellers of San Antonio. In a city long dominated by an ultra-conservative political machine, workers stood up, despite the fact that the business community, the police, the media, the church and even some elements within the Latino organizations and unions were against them. They showed all workers how to confront employer abuses and police harassment and political witch-hunts. Their brave stand should serve as an example to all of us, especially in the difficult days ahead, when the powerful will inevitably set similar traps for the labor movement again. One of the weapons used against the strike was the tactic of Red-baiting. At the beginning of the strike, the strikers had unanimously elected as their spokesperson a young woman named Emma Tenayuca. A dynamic speaker with a magnetic personality, Tenayuca was a member of the small Communist Party chapter in Texas. The workers’ enemies attacked all the strikers because of Tenayuca’s political associations. In order to deprive the strike’s enemies of a pretext with which to attack the workers, Emma Tenayuca eventually decided to step aside from role as chief spokesperson for the strikers. (She continued as one of the strike’s most stalwart leaders on the ground.)

On March 8, 1938, the pecan shellers returned to work for the wages that originally sparked the strike – pending the decision of a three-person arbitration board. On April 13, 1938, the board rendered a decision giving the workers a slight wage increase and extending recognition to Local 172 as the workers’ legal bargaining agent.

On October 24, 1938, a new federal law went into effect raising the minimum wage. The Southern Pecan Shelling Company and the local union petitioned for an exemption to this minimum wage. When their requests were denied, the pecan shelling companies quickly began to mechanize.

By 1941, about 10,000 of the 12,000 unskilled workers who had made up San Antonio’s pecan shelling industry at the time of the strike had lost their jobs permanently. By 1948, Pecan Shelling Workers Union Local 172 had disappeared.

The massive job loss which followed the strike does not diminish the significance of the strike itself. The courageous fight of the pecan shellers of San Antonio paved the way for the battles waged by other agricultural and food workers in the Southwest. Their victories would never have been achieved without the valiant example set by the pecan shellers of San Antonio. In a city long dominated by an ultra-conservative political machine, workers stood up, despite the fact that the business community, the police, the media, the church and even some elements within the Latino organizations and unions were against them. They showed all workers how to confront employer abuses and police harassment and political witch-hunts. Their brave stand should serve as an example to all of us, especially in the difficult days ahead, when the powerful will inevitably set similar traps for the labor movement again.

The articles on this page are written by Chris Mahin for the Education and Mobilization Department of the Chicago & Midwest Regional Joint Board of UNITE HERE and originally appeared on the Joint Board’s website.

Special thanks to Brother Mahin for allowing the Pennsylvania Federation access to his writings.

|