Labor fought slavery in the Civil War; How do we fight it now?

Thirteenth Amendment, December 1865

The main headline proclaimed the news in large capital letters set in thick black type: “THE CONSUMMATION!”

Below, only slightly smaller headlines continued: “Slavery Forever Dead in the United States. … No Human Bondage After Dec. 18, 1865.”

The New York Times had good reason to use dramatic headlines in its Dec. 19, 1865 edition. Those headlines reported a momentous development: Slavery was now illegal throughout the whole of the United States. U.S. Secretary of State William Seward had signed a proclamation the previous day announcing the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

The Thirteenth Amendment states that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Like all proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution, it had to be passed by a two-thirds majority of each house of Congress and then ratified by three-quarters of the states. The Thirteenth Amendment was passed by a two-thirds majority in the U.S. Senate in 1864 and then by a two-thirds majority of the House in early 1865. When Georgia became the 27th state to ratify the amendment in early December 1865, the conditions were met for Seward to announce that the measure had become the law of the land.

December 2010 marks 145 years since the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. This December, it’s important that we consider what its passage means for today.

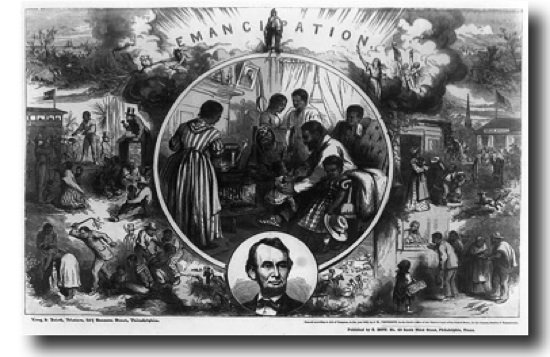

It was the Thirteenth Amendment – not Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation – which made chattel slavery illegal throughout the whole of the United States. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 granted freedom only to slaves in territory controlled by those in rebellion against the federal government. While the Emancipation Proclamation was an important blow against the slave-owners’ rebellion, it excluded hundreds of thousands of slaves in slave states which never seceded from the Union (like Delaware and Kentucky) and in parts of Virginia and Louisiana then occupied by the Union Army.

However, the sad truth is that while the Thirteenth Amendment made slavery and involuntary servitude illegal in the United States, it did not end slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States, nor did it bring about equality for the former slaves or their descendants.

Anyone who works in a factory where there is mandatory overtime knows that involuntary servitude still exists in parts of this country. So does slavery. Many undocumented immigrant workers, for instance, work in sweatshops in conditions which amount to outright slavery. For millions of workers around the world, the growth of free trade for employers has meant an increase in slavery for workers. Today, those of us working in the United States find ourselves in a situation somewhat similar to the textile workers of Fall River, Massachusetts in 1844. They were told by the mill owners: “You must work as long and as cheap as the Slaves of the South, in order to compete with the Southern manufacturer.” For us, the “South” is the global South – the sweatshops outside the United States where workers are compelled to work under slave-labor conditions.

Before the Civil War, the most farsighted leaders of the U.S. labor movement spoke out against slavery, prompted by a combination of moral outrage and the practical necessity to oppose measures which would tend to drive the conditions of free laborers down to the level of the slaves. The great opponent of slavery Thomas Wentworth Higginson was correct when he wrote in his memoirs that the anti-slavery cause was “far stronger for a time in the factories and shoe shops [of New England] than in the pulpits or colleges.”

When Lincoln called for volunteers after the secessionists attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861, carpenters, painters, shoemakers, tailors, clerks, mill operatives, printers, and other workers left their jobs and joined the Union’s military forces.

Immigrant workers comprised 24 percent of the Union Army, and played an important role in the war. The De Kalb regiment was made up entirely of German clerks. The Garibaldi Guard was composed of Italian workers. The Polish Legion was organized by Polish workers. The “Fighting 69th” – the 69th Regiment from New York – included many Irish immigrant workers.

Entire local unions enlisted in response to the attack on Fort Sumter. A Philadelphia local union entered the following in its minutes: “It having been resolved to enlist with Uncle Sam for the war, this Union stands adjourned until the Union is safe or we are whipped.”

Slaves ran away, found their way to the Union Army’s lines, and insisted that they be allowed to join the army and fight.

All this is part of labor history, and of our common heritage. We should never forget that hundreds of thousands of workers had to spill their blood to place the Thirteenth Amendment into the Constitution of the United States. Today, our challenge is to figure out how to make this country implement that amendment in fact, not just in words -- in the midst of a new economy where there is slavery all around us. The workers of the Civil War era were not afraid to envision a completely new world; we should not be afraid to do so either.

The articles on this page are written by Chris Mahin for the Education and Mobilization Department of the Chicago & Midwest Regional Joint Board of UNITE HERE and originally appeared on the Joint Board’s website.

Special thanks to Brother Mahin for allowing the Pennsylvania Federation access to his writings.

|