January 1936: The sit-down strike introduces a new tactic

It was a little like staging the Boston Tea Party inside a factory.

Exactly 75 years ago this month, bold trade unionists introduced a dramatic new tactic to this country: the sit-down strike.

This innovative method of fighting made its first major appearance in Akron, Ohio in January 1936. For several weeks, Firestone Tire & Rubber Company had been trying to speed up production in the truck tire department at its Plant One facility in Akron, a move the tirebuilders vehemently opposed. In response, the plant manager sent a company spy into the department to figure out ways to speed up the line. The company agent tried to provoke a fight with Clayton Dicks, a union committeeman in the department. The company accused Dicks of punching the company spy and knocking him out, and suspended Dicks without pay for an entire week.

Outraged at the suspension, union tirebuilders demanded that Dicks be reinstated. When the company refused, the tirebuilders stopped work en masse.

In her book “Industrial Valley,” Ruth McKenny described what happened next:

“Instantly, the noise stopped. The whole room lay in perfect silence. The tirebuilders stood in long lines, touching each other, perfectly motionless, deafened by the silence. … Out of the terrifying quiet came the wondering voice of a big tirebuilder near the windows: ‘Jesus Christ, it’s like the end of the world.’ He broke the spell, the magic moment of stillness. For now his awed words said the same thing to every man, ‘We done it! We stopped the belt! By God, we done it!’ And men began to cheer hysterically, to shout and howl in the fresh silence. … ‘John Brown’s body,’ somebody chanted above the cries. The others took it up. ‘But his soul,’ they sang, and some of them were nearly weeping, racked with sudden and deep emotion, ‘but his soul goes marchin’ on.’ ”

The sit-down began at exactly 2 a.m. on January 29, 1936 in the truck tire department. It immediately spread to all the other departments in Firestone Plant One in Akron. By the end of the first day, all four of Plant One’s shifts had participated. (Plant One operated with four shifts of six hours’ duration each.)

For the next three days, workers moved freely throughout the plant. They occupied the foreman’s office and issued union cards. They did no work; the machines stood still. Management officials could do nothing (except become increasingly more furious). By the end of the third day, workers at Firestone Plant Two were ready to support Plant One with their own sit-down. For the next three days, workers moved freely throughout the plant. They occupied the foreman’s office and issued union cards. They did no work; the machines stood still. Management officials could do nothing (except become increasingly more furious). By the end of the third day, workers at Firestone Plant Two were ready to support Plant One with their own sit-down.

Firestone officials settled the strike quickly, worried that the strike’s demands would grow to include recognition of the United Rubber Workers, an industrial union founded just months before. Fifty-five hours after production had ceased, Clayton Dicks was reinstated with back pay at half his normal rate for the period of the suspension and the sit-downers were paid at the same rate for the period of the sit-down. The company agreed to negotiate about the base rate.

The battle at Firestone was the first time the sit-down strike was used in a major industrial confrontation in the United States. The Akron tirebuilders had learned about the tactic from Alex Eigenmacht, an immigrant union printer in Akron. He had taken part in an “inside strike” of printers in Sarajevo, Serbia, and explained the reasoning behind it to a delegation of Akron tirebuilders who visited him to ask for advice.

Firestone’s sit-down inspires others

Within days, the Firestone sit-down inspired similar actions at Akron’s other huge tire manufacturers – Goodyear and B.F. Goodrich.

Goodrich workers sat down on February 8 and 9, 1936. They were protesting a cut in the base rate of pay. The company settled quickly (to avoid a battle over union recognition). On Friday, February 14, 1936, the tirebuilders of Goodyear’s Plant Two, Department 251-A, turned off their machines and sat down to protest the lay-off of 70 men. The sit-downers were worried that the layoffs marked the first step in an effort by the company to end the six-hour day and replace it with an eight-hour day.

By the end of the first day of the Goodyear sit-down, it was clear to the workers that the company was not going to react the way that the management at Firestone and Goodrich had done. At 9:30 p.m. on February 14, Fred Climer, the Goodyear personnel manager, notified the 137 Goodyear sit-down strikers that they were all fired. Then he locked the strikers inside the tirebuilding room.

On Monday night, February 17, 1936, Goodyear’s workers voted to strike over the issues of the layoffs, speed-up, and hours of work. Within days, the company’s enormous Akron facility was shut down. In a stunning display of organization, the union ensured that each of the 160 gates stretching over 18 miles of company property were guarded by pickets 24 hours a day. Almost immediately, 160 picket shanties were built, picket line supervisors appointed, and strike rallies organized.

The strike continued for 33 days through one of the worst winters in Ohio history. Finally, the strike ended on March 21, 1936. As a result of the agreement, the 137 sit-downers were reinstated, and an agreement was reached limiting Goodyear’s discretion to increase hours without conceding any restrictions on the workers’ right to strike.

These victories only intensified the struggle for control of the shop floor. The sit-down movement continued through the end of 1936 as Akron workers staged at least 52 sit-down strikes between the Goodyear settlement and the beginning of 1937.

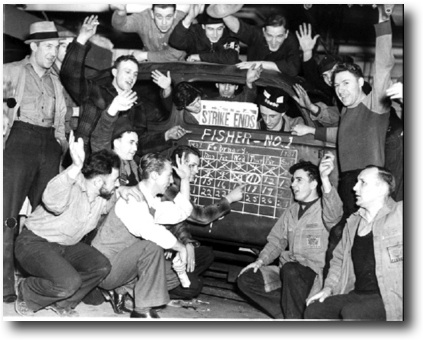

Eventually, the tactic of the sit-down spread to the auto industry and led to other dramatic events, such as the Great Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1937. From the auto industry, it spread to many different places of work. Between 1936 and 1939, American workers engaged in 583 sit-down strikes of at least one day’s duration.

Sit-down strikes change people’s thinking

The wave of sit-down strikes during the 1930s changed this country profoundly. The act of sitting down altered the lives of the people who took that step. “Now we don’t feel like taking the sass of any snot-nose college-boy foreman,” one worker said, describing the mood in the plant after the sit-downs. “Now we know our labor is more important than the money of stockholders, than the gambling in Wall Street, than the doings of the managers and foremen.”

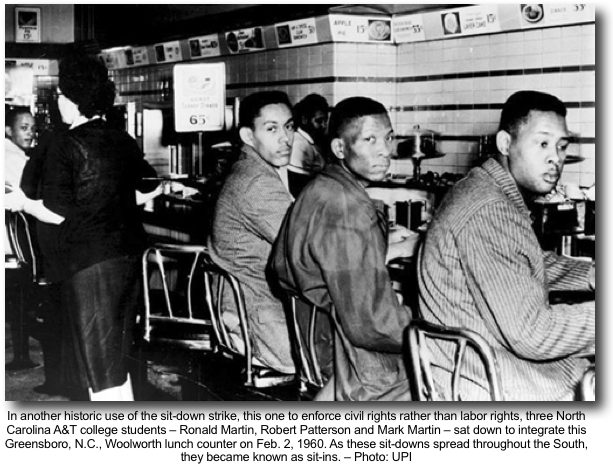

The sit-down wave also provoked an intense public debate over whether it was morally right to occupy the capitalists’ property and about which set of rights is more important, human rights or property rights. The champions of the sit-down strike pointed out that they were continuing a long tradition in this country of defending human rights against the tyranny of the powerful. When newspaper columnists and political officials denounced the sit-downers for doing things which were illegal, they defiantly reminded the public that the Boston Tea Party and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry were illegal too.

“It was once unlawful to picket,” one union activist pointed out. “Every right, every liberty, every privilege … has been won … by men who dared to defy some law – by men who dared to be ‘illegal.’” The UAW called on its organizers to remind people of those who have defied the status quo. “Destroy fear of jail by recalling the prison terms of William Penn, John Brown and other famous Americans,” a UAW statement urged.

The wave of sit-down strikes helped pave the way for the emergence of a social contract between capital and part of labor. The leaders of the CIO argued that employers were better off granting legal recognition to unions than running the risk of having workers physically occupy their factories. “A CIO contract is adequate protection,” declared John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers, “against sit-downs, lie-downs, or any other kind of strike.”

A social contract emerges

Before the 1930s were over, the owners of the most important industries in the United States had come to understand that John L. Lewis was right. The leaders of the capitalist class began to work with the most “responsible” labor leaders to ensure a system of labor peace in this country – one in which sit-down strikes would “not be necessary.” A social contract was established – at least for some workers. Workers in the large auto, steel and rubber factories were unionized, but the workers in the auto parts supplier plants, the small iron foundries, and in the canneries and fields were not. The result was a labor peace that fenced out more workers than it fenced in.

In the heyday of this social contract, having a union job meant receiving good wages, access to health care, and the possibility of owning a home and eventually drawing a pension. This process can be seen in the rubber industry after the sit-down strikes of the 1930s. In 1946, the United Rubber Workers succeeded in obtaining a general wage increase with the “Big Four” of the rubber industry – Goodyear, U.S. Rubber, Firestone and Goodrich – in one set of negotiations. The first companywide agreement came in 1947. By 1948, all the major rubber companies had master agreements. In 1949, the United Rubber Workers began to demand better pensions. In 1982, the URW went on strike against what had become the “Big Five” (with the rise of Uniroyal) and 23 independent companies, and won major wage increases and benefit improvements.

An industry begins to decline

During the prime years of the social contract, industry was still booming in the United States. In 1950, the corporate offices of five of the six largest tire companies in the United States were located in Akron. That year, Ohio firms produced more than one-third of the tires and about 30 percent of all other rubber products used in the United States.

However, by the late 20th century, the rubber industry went into decline in Ohio. Many production facilities moved to other parts of the United States, especially the South. The same forces of globalization, deindustrialization, and the rise of electronics which have devastated other industries began to hit the rubber industry. In 1988, the Bridgestone Corporation, a Japanese company, purchased Firestone. In 1994, Bridgestone/Firestone unleashed what came to be known as the “war of ’94” against its employees, demanding that workers accept 12-hour shifts, increased worker contributions to the health insurance plan, and pay based on productivity.

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company provides another example of this process. The company now employs about 80,000 people in 28 countries. In 2003, when the company was on the verge of bankruptcy, active union members and retirees went out of their way to ensure the company’s survival. The United Steel Workers of America – which had merged with the United Rubber Workers several years before -- negotiated a contract which allowed Goodyear to cut wages, health care benefits, and pensions, and to close the Huntsville, Alabama plant. Goodyear workers agreed to all that in exchange for job security commitments. In 2005, Goodyear posted its highest profits in seven years and gave its top executives large bonuses. Then, in 2006, Goodyear broke its promise, announced the closing of its Tyler, Texas plant – with 1,100 jobs – and insisted that the workers agree to even more concessions.

More than 15,000 members of the United Steel Workers went on strike against Goodyear on October 5, 2006. Workers from 15 plants across the United States and Canada walked out to protest Goodyear’s unfair contract proposals. (One of the union locals currently on strike is Local 2 in Akron, the scene of the 1936 strike against Goodyear.) The current walk-out is a response to Goodyear’s unprecedented attempt to wash its hands of its health care obligations to current and future retirees. Retired workers at Goodyear, many of whom experience medical conditions caused by their job, would soon be left without health-care coverage if Goodyear gets its way. On October 31, 2006, Goodyear brought in “temporary replacement workers” to take the jobs of union workers. On Dec, 15, 2006, the United Steel Workers union and its allies distributed leaflets at over 100 Goodyear distributorships and retail stores across the United States. This National Day of Action helped stall Goodyear’s offensive and set the stage for a new contract proposal that may settle the strike.

The social contract is torn to pieces

Clearly, the social contract is now being torn to pieces. Given this, labor cannot continue to fight in the way that it did when times were good for the best-paid workers. We will have to develop new tactics, new forms of organization – and a new outlook.

While our tactical situation is not the same as that of the sit-down strikers, those workers still have much to teach us. We should honor their bravery. We should emulate their willingness to take the good suggestion of an immigrant worker and use a new tactic in the battle on the shop floor. Perhaps most of all, we should absorb their defiant attitude, their refusal to be intimidated. When the mass media of their day – the right-wing newspapers – denounced their actions as illegal, the sit-downers proudly pointed to the illegality of the Boston Tea Party and of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, and described their sit-down strikes as continuations of those noble efforts.

The sit-down strikers openly proclaimed that the human rights of the workers who built tires and automobiles and other commodities were more important than the private property of the factory owners. The sit-downers were crystal clear on the necessity to take the moral offensive against the enemy. They saw the little communities they built for a few days inside the factories in the course of seizing control of their workplaces as a model of how human beings could treat one another when the factory owners were no longer in charge. The sit-down strikers made no apologies for fighting for a new world; neither should we.

The articles on this page are written by Chris Mahin for the Education and Mobilization Department of the Chicago & Midwest Regional Joint Board of UNITE HERE and originally appeared on the Joint Board’s website.

Special thanks to Brother Mahin for allowing the Pennsylvania Federation access to his writings.

|